[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Hungary's Price Caps Have to Be Phased Out, Minister Says U.S News & World Report Moneyfrom "price" - Google News https://ift.tt/klDErVJ

via IFTTT

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Hungary's Price Caps Have to Be Phased Out, Minister Says U.S News & World Report Money

Nearly 50% of houses in Seattle were sold below their initial asking price, nearly double the amount from July 2021, across an overall cooling housing market nationwide, according to Redfin data.

A high share of home sellers dropped their asking price in July, particularly in pandemic boomtowns like Seattle and Portland, as they struggled to match their expectations with the market.

Western Washington had approximately 9,000 active listings in June, up close to 60% year-over-year. Pending and closed sales are down year-over-year (a decrease of 11.7%), but up from the previous month (an increase of 8.2%).

Redfin settles lawsuit alleging housing discrimination

Still, the median home price in Seattle rose 7.5% year over year, hitting $860,000 in July.

More than 15% of home sellers dropped their asking price in every major U.S. metro.

Boise, Idaho leads the country with 69.7% of homes requiring a price drop from its original price. Denver, Salt Lake City, Tacoma, Tampa, Sacramento, Indianapolis, and Phoenix are north of 50%.

“Individual home sellers and builders were both quick to drop their prices early this summer, mostly because they had unrealistic expectations of both price and timelines,” said Boise Redfin agent Shauna Pendleton in a prepared statement. “They priced too high because their neighbor’s home sold for an exorbitant price a few months ago, and expected to receive multiple offers the first weekend because they heard stories about that happening.”

In McAllen, TX, 15.7% of sellers dropped their asking price, a smaller share than any other metro. It’s followed by Newark, NJ (15.8%), Miami (18.5%), Honolulu (18.5%), and Bridgeport, CT (18.8%).

The share of homes with a price drop increased from a year earlier in all but three metros, all of which are in Illinois. The share dipped from 28.2% to 22.3% in Lake County, 27.3% to 22% in Elgin, and 26.4% to 21.3% in Chicago.

“My advice to sellers is to price their home correctly from the start, accept that the market has slowed, and understand that it may take longer than 30 days to sell,” said Pendleton. “If someone is selling a nice home in a desirable neighborhood, they shouldn’t need to drop their price.”

In July 2021, Fresno, Calif. led the nation with 37.9% of houses requiring a price drop in order to sell. This percentage would rank 32nd among cities this year.

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

European Energy Prices Plunge as EU Plans to Intervene in Crisis BloombergBENGALURU, Aug 30 (Reuters) - Skyrocketing U.S. house prices will rise at their weakest pace in more than a decade next year as worsening affordability dents demand, according to analysts polled by Reuters, who said prices need to fall in double digits to be fairly valued.

A frenzy for homes in short supply over the past two years during the pandemic, backed by near-zero interest rates, has inflated house prices over 40% during that time, shutting out many first-time buyers.

But with rising mortgage rates following a cumulative 225 basis points of interest hikes by the U.S. Federal Reserve since March and more expected over the coming months, a slowdown was inevitable in a sector highly sensitive to the cost of borrowing. read more

The Aug. 12-30 poll of around 30 property analysts showed average U.S. house prices would rise 14.8% on average this year, slower than the current pace of around 20% but higher than the May poll's prediction of 10.3%.

Those forecasts are based on the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller composite index of 20 metropolitan areas.

House prices were then expected to rise only 2.0% next year, less than half of what was predicted in May. If realized, it would be the lowest pace since 2012 and below headline consumer inflation for the first time in over a decade.

"Home price appreciation is set to come to a screeching halt under the weight of poor housing affordability and a deteriorating economic and financial environment," said Scott Anderson, chief economist at Bank of the West.

"This correction could happen all at once during a recession or gradually over time. No matter how you measure it today, home prices are extremely expensive."

The predicted slowdown was in line with a separate Reuters poll which showed a 50% chance of a U.S. recession within the next two years.

At its worst in decades, affordability is unlikely to improve significantly anytime soon as the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage rate was expected to remain above 5% at least until 2024.

Most analysts also agreed U.S. houses are highly overvalued.

When asked to rate average U.S. house prices on a scale of 1 to 10 where 1 was extremely cheap, 5 was priced about right and 10 extremely expensive, the median forecast of 26 contributors rated it 8. Four contributors said 10.

Nearly 80% of respondents, 16 of 21, who answered a separate question said prices needed to fall 10% or more to be fairly valued, including two who said 30% or above.

But there were notable inconsistencies in the responses. Some rating the market extremely overvalued provided modest figures to bring average prices to fair value while others who saw it less overvalued said a larger correction was required.

The last time U.S. house prices fell in double digits was during the global financial crisis, where cumulatively they fell by around one-third and in some cases more during 2007-09.

Although around one-third of contributors predicted an outright fall in prices at some point over the next two years, all were in single digits.

Most respondents said it would take several years for house prices to be fairly valued with a few saying it would never happen.

"Housing prices have outpaced inflation by a significant margin. ... Prices are not likely to come down into 'fairly valued' territory for the foreseeable future," said Crystal Sunbury, senior real estate analyst at RSM, a U.S.-based consulting firm.

Activity is already slowing as single-family housing starts, which account for the biggest share of homebuilding, fell to its lowest level since June 2020 and housing sentiment hovers around multiyear lows. read more

Existing home sales, which comprise about 90% of total sales and are currently at their lowest since May 2020, were predicted to decline further and average 4.73 million units over the coming year. read more

"Buyers remain spooked by the rapid rise in financing costs they have seen so far this year," said Matthew Gardner, chief economist at Windermere Real Estate.

"The cautious attitude will continue until spring of 2023 when sales will pick up again, albeit modestly."

(For other stories from the Reuters quarterly housing market polls:)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

Check out what's clicking on FoxBusiness.com.

The Biden administration has continued private negotiations with Western allies to implement a global cap on the price of Russian oil to avoid a potential gas price disaster.

The Department of the Treasury, which is leading the effort, said it continues to negotiate the policy which it has argued is necessary to ensure global and U.S. oil prices don't surge in the coming months. The agency, which has engaged in discussions with a number of nations both in and out of the G7, could reach a resolution with partners as soon as September.

"A price cap on Russian oil will both deny Putin money for his war machine and put downward pressure on the high oil costs caused by Russia’s unprovoked war against Ukraine," a Treasury Department spokesperson told FOX Business in a statement.

"We continue to have productive discussions with the G7 and other allies and partners, who share a common interest in helping consumers by preventing further disruptions to the global supply of oil and reducing revenue to the Kremlin," the spokesperson added.

EUROPE'S GREEN ENERGY POLICIES STRENGTHENED PUTIN, MICHAEL SHELLENBERGER SAYS

President Biden speaks with Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen during a cabinet meeting. (Sarah Silbiger for The Washington Post via Getty Images / Getty Images)

In late June, the U.S. and G7 allies announced their intention to implement the price cap, which would effectively disallow international oil buyers to purchase Russian product for a price greater than some figure set during negotiations. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said the policy would limit Russian government revenue and stabilize global markets.

For example, the nations could set a cap of $50 per barrel of Russian oil even as the benchmark price of oil remains near $100 a barrel, an unprecedented move forcing all purchases of the Russian product to come at a significant discount. Much-needed oil would continue to flow while Russia's government would take a financial hit.

NETHERLANDS JOIN GERMANY, AUSTRIA, ITALY IN REVERTING TO COAL AMID RUSSIA'S INVASION OF UKRAINE

"Yeah, this is novel, but, my gosh, we are in a novel situation," David Wessel, the director of the Brookings Institution's Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, told FOX Business in an interview. "It's a difficult situation for the West. On one hand, we want to sanction Russia. On the other hand, we want to prevent an increase in oil prices that is so steep that it pushes the rest of the world into recession."

Russian President Vladimir Putin is pictured in Moscow, Russia, on March 25. (Mikhail Klimentyev, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP, file / AP Images)

Failing to negotiate a price cap with a stipulation that allows insurance on vessels abiding by the set price point, therefore, could decrease global oil supplies and lead to much higher prices, Wessel added.

Wessel said it is important to ensure Russian oil continues to flow to ensure adequate supply. Russian industry accounts for 10% of the world's petroleum supply and produces about 10 million barrels per day of oil (mbd), exporting roughly 5 mbd of oil and another 3 mbd of petroleum products like gasoline, according to a Federal Reserve report from March.

BIDEN SAYS G-7 WILL BAN RUSSIAN GOLD IMPORTS OVER WAR ON UKRAINE

The European Union and U.K., though, adopted a package of sanctions targeting Russia's economy restricting Russian oil imports and, potentially more importantly, prohibiting operators from insuring or financing the transport of Russian oil on June 3.

Dean Cheng, Senior Research Fellow for Asian Studies at the Heritage Foundation, discusses China's recent investments in Russia and their growing space program

"It's a very delicate equation here," Wessel continued.

"When the Europeans said, ‘Not only are we not going to buy any oil from Russia, but we are going to forbid our insurance companies on the continent and in the U.K. from insuring or reinsuring or financing shipments of Russian oil,’ that made the U.S. very nervous because, if enforced, that would make it almost impossible for Russia to export oil and to the extent that it could export oil, it would be at a very reduced supply," he said.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ON FOX BUSINESS

Kevin Book, a National Petroleum Council member and managing director of ClearView Energy Partners, noted that tankers carrying Russian crude oil would still be able to hire an insurer of last resort, but said the global market would still tighten if a price cap deal wasn't reached.

"It narrows the availability of ships, reduces the overall supply," Book told FOX Business in an interview. "It doesn't necessarily imply a catastrophic shutdown of the flows, but a tightening of a market that is already tight."

“We saw [home] prices moving up very very strongly for the last couple of years. So that changes now. And rates have moved up,” Powell told reporters in June. “We are well aware that mortgage rates have moved up a lot. And you are seeing a changing housing market. We are watching it to see what will happen. How much will it really affect residential investment? Not really sure. How much will it affect housing prices? Not really sure.”

“I’d say if you are a homebuyer, somebody or a young person looking to buy a home, you need a bit of a reset. We need to get back to a place where supply and demand are back together and where inflation is down low again, and mortgage rates are low again.”

It’s clear the Fed’s “housing reset” will give homebuyers more options (i.e. rising inventory) and more breathing room (i.e. fewer bidding wars). The question mark—which Powell acknowledged in June—is will it push home prices lower? Historically speaking, home prices remain sticky until economics forces sellers’ hand.

To better understand where home prices might be headed, Fortune reached out to CoreLogic to see if the firm would provide us with their updated August assessment of the nation’s largest regional housing markets. To determine the likelihood of regional home prices dropping, CoreLogic assessed factors like income growth projections, unemployment forecasts, consumer confidence, debt-to-income ratios, affordability, mortgage rates, and inventory levels. Then CoreLogic put regional housing markets into one of five categories, grouped by the likelihood that home prices in that particular market will fall over between June 2022 and June 2023. Here are the groupings the real estate research firm used for the August analysis:

Between June 2022 and June 2023, CoreLogic predicts U.S. home prices are poised to rise another 4.3%. But that's nationally. Regionally, some markets are at high risk of falling prices.

Among the 392 regional housing markets it looked at, CoreLogic found 125 markets have a greater than 50% chance of seeing local home prices decline over the next 12 months. In July, CoreLogic found 98 markets had a greater than 50% chance of a home price decline over the next 12 months. In June, 45 markets were at-risk. In May, just 26 markets fell into that camp.

Why does CoreLogic keep slashing its risk assessment? It boils down to souring U.S. housing market data. On a year-over-year basis, existing home sales and new home sales are down 20.2% and 29.6%, respectively. That's the sharpest housing activity contraction since 2006.

“Probability of home price decline continues to intensify as mortgage rates hit a new high in June and housing demand took a considerable dip," Selma Hepp, deputy chief economist at CoreLogic, tells Fortune.

"Price decline risk remains concentrated in regions that saw exceedingly high home price growth over the last two years, but not the same level of population and income growth, and areas that are historically more sensitive to increase in mortgage rates and recession signals,"

Of those 392 regional housing markets that CoreLogic measured, 67 markets in August have "very low" odds of falling home prices over the coming year. Another 133 housing markets are in the "low" group and 67 markets are in the "medium" group. CoreLogic put 85 markets in the "high" camp. CoreLogic categorized 40 markets as having "very high" odds of falling home prices over the coming year. That includes major markets like Boise, San Francisco, and Lake Havasu City.

The real estate industry should always be on high alert when the Federal Reserve shifts into inflation-fighting mode. After all, the sector is the most rate sensitive sector in the economy. That said, some regional markets should be on higher alert than others. Historically speaking, when a housing cycle "rolls over," it's normally the significantly "overvalued" housing markets that are at the highest risk of home price corrections.

According to CoreLogic, 75% of the nation's regional housing markets are "overvalued" relative to underlying economic fundamentals. Many of these frothy markets, like Boise, are at the highest risk of a price correction. However, there's one big exception: San Francisco. While CoreLogic says the Bay Area is at "very high" risk of falling home prices, it says the market isn't overvalued. What's going on? High-cost tech hubs, like San Francisco and Seattle, are getting hit hard by the tech slowdown. Not only are their high-end real estate markets more rate sensitive, but so are their tech sectors.

A growing chorus of research firms agree with CoreLogic that markets like Boise and San Francisco are at-risk of falling home prices. However, CoreLogic putting Phoenix—a market where inventory has spiked back to 2019 levels—as "low risk" for a price decline is eyebrow raising. Research groups like Moody's Analytics and John Burns Real Estate Consulting predict home prices will fall in Phoenix over the coming year.

"People don't expect prices [in Phoenix] to increase fast, or at all, anymore. The median metro Phoenix house price fell the last two months. If prices continue to fall for long enough, people will eventually expect prices to continue to fall in the future and then we could see the flip side of the 2021 housing market," John Wake, an independent real estate analyst based in Phoenix, tells Fortune.

Hungry for more housing data? Follow me on Twitter at @NewsLambert.

Sign up for the Fortune Features email list so you don’t miss our biggest features, exclusive interviews, and investigations.

Apple's Far Out launch event is scheduled for Sept. 7. This means that the iPhone 14's arrival is likely just a week and a half away. But with a slew of upgrades expected to come alongside the new iPhone, how much will it cost?

The successor to the 2021 iPhone 13 is expected to sport a notchless display, a 48-megapixel camera on the high-end models and a new 6.7-inch iPhone 14 Max option, if the leaks and rumors are to be believed.

All of this may come at a price increase to the tune of $100, according to a prediction from Wedbush analyst Dan Ives, as reported on Ped30. This is in line with forecasts previously shared by analysts with The Sun, which suggested that Apple's entire supply chain is seeing price increases. Apple didn't respond to a request for comment.

Apple didn't make any price changes between the iPhone 12 and iPhone 13, but those two generations of iPhones are also fairly similar. It's reasonable to think that bigger upgrades could come with higher prices. But Apple may keep the price the same to remain competitive with Android devices like the Samsung Galaxy S22 and Google's Pixel 6 line.

Apple usually releases its new iPhones in September shortly after unveiling them, although some new size options have launched later than usual in years past. Apple supplier Foxconn is said to have gone on a hiring spree to prepare for the launch, according to the South China Morning Post.

Read more: The iPhone's Future Could Depend on These Breakthrough Technologies

There hasn't been any official word iPhone 14's price yet, and Apple never provides public information about its future products before it announces them. That means the only clue we have is the iPhone 13's pricing structure, shown below.

| 128GB | 256GB | 512GB | 1TB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPhone 13 Mini | $699 | $799 | $999 | N/A |

| iPhone 13 | $799 | $899 | $1,099 | N/A |

| iPhone 13 Pro | $999 | $1,099 | $1,299 | $1,499 |

| iPhone 13 Pro Max | $1,099 | $1,199 | $1,399 | $1,599 |

Apple maintained a similar pricing structure for the iPhone in 2020 and 2021, so there's a chance it might continue to do so in 2022. However, rumors that Apple could scrap the iPhone Mini and replace it with another cheaper version of the 6.7-inch iPhone complicates things a bit. That's according to reports from analyst Ming-Chi Kuo (via 9to5Mac) and Nikkei Asian Review.

That new addition to the lineup is said to be a larger version of the iPhone 14, likely to be called the iPhone 14 Max. If Apple keeps the same $800 price for the standard iPhone, it seems reasonable that the iPhone 14 Max could cost $900. That would put it right in between the $1,000 iPhone 14 Pro and $1,100 iPhone 14 Pro Max, assuming the iPhone 14 is priced similarly to the iPhone 13.

Read more: It Might Finally Be Time for Foldable Phones

But reliable analyst Ming-Chi Kuo predicts that this so-called iPhone 14 Max will cost less than $900, according to 9to5Mac, suggesting Apple might change up its pricing strategy. Apple has reshuffled its pricing before to stay competitive: 2019's iPhone 11 was notable for its $699 starting price that undercut the previous year's iPhone XR by $50.

Here's what the iPhone 14's pricing could look like across models based on the iPhone 13's price structure.

| 128GB | 256GB | 512GB | 1TB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPhone 14 | $799 | $899 | $1,099 | N/A |

| iPhone 14 Max | $899 | $999 | $1,199 | N/A |

| iPhone 14 Pro | $999 | $1,099 | $1,299 | $1,499 |

| iPhone 14 Pro Max | $1,099 | $1,199 | $1,399 | $1,599 |

For more, check out all the iPhone 14 rumors we've heard so far, including design changes and release date. You can also take a look at CNET's iPhone 14 wish list.

NEW YORK (AP)—A mint condition Mickey Mantle baseball card sold for $12.6 million Sunday, blasting into the record books as the most ever paid for sports memorabilia in a market that has grown exponentially more lucrative in recent years.

The rare Mantle card eclipsed the record just posted a few months ago—$9.3 million for the jersey worn by Diego Maradona when he scored the contentious “Hand of God” goal in soccer’s 1986 World Cup.

It easily surpassed the $7.25 million for a century-old Honus Wagner baseball card recently sold in a private sale.

And just last month, the heavyweight boxing belt reclaimed by Muhammad Ali during 1974′s “Rumble in the Jungle” sold for nearly $6.2 million.

All are part of a booming market for sports collectibles.

Prices have risen not just for the rarest items, but also for pieces that might have been collecting dust in garages and attics. Many of those items make it onto consumer auction sites like eBay, while others are put up for bidding by auction houses.

Because of its near-perfect condition and its legendary subject, the Mantle card was destined to be a top seller, said Chris Ivy, the director of sports auctions at Heritage Auctions, which ran the bidding.

Some saw collectibles as a hedge against inflation over the past couple years, he said, while others rekindled childhood passions.

Ivy said savvy investors saw inflation coming down the road—as it has. As a result, sports memorabilia became an alternative to traditional Wall Street investments or real estate—particularly among members of Generation X and older millennials.

“There’s only so much Netflix and ‘Tiger King’ people could watch (during the pandemic). So, you know, they were getting back into hobbies, and clearly sports collecting was a part of that,” said Ivy, who noted an uptick in calls among potential sellers.

Add to that interest from wealthy overseas collectors and you have a confluence of factors that made sports collectibles especially attractive, Ivy said.

“We’ve kind of started seeing some growth and some rise in the prices that led to some media coverage. And I think it all it all just kind of built upon itself,” he said. “I would say the beginning of the pandemic really added gasoline to that fire.”

Before the pandemic, the sports memorabilia market was estimated at more than $5.4 billion, according to a 2018 Forbes interview with David Yoken, the founder of Collectable.com.

By 2021, that market had grown to $26 billion, according to the research firm Market Decipher, which predicts the market will grow astronomically to $227 billion within a decade—partly fueled by the rise of so-called NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, which are digital collectibles with unique data-encrypted fingerprints.

Sports cards have been especially in demand, as people spent more time at home and an opportunity arose to rummage through potential treasure troves of childhood memories, including old comic books and small stacks of bubble gum cards featuring marquee sports stars.

That lure of making money on something that might be sitting in one’s childhood basement has been irresistible, according to Stephen Fishler, founder of ComicConnect, who has watched the growing rise—and profitability—of collectibles being traded across auction houses.

“In a nutshell, the world of modern sports cards has been going bonkers,” he said.

The Mantle baseball card dates from 1952 and is widely regarded as one of just a handful of the baseball legend in near-perfect condition.

The auction netted a handsome profit for Anthony Giordano, a New Jersey waste management entrepreneur who bought it for $50,000 at a New York City show in 1991.

The switch-hitting Mantle was a Triple Crown winner in 1956, a three-time American League MVP and a seven-time World Series champion. The Hall of Famer died in 1995.

“Some people might say it’s just a baseball card. Who cares? It’s just a Picasso. It’s just a Rembrandt to other people. It’s a thing of art for some people,” said John Holden, a professor in sports management law at Oklahoma State and amateur sports card collector.

Like pieces of art that have no intrinsic value, he said, when it comes to sports cards, the worth is in the eye of the beholder—or the pocketbook of the potential bidder.

“The value,” Holden said, “is whatever the market’s willing to support.”

More MLB Coverage:

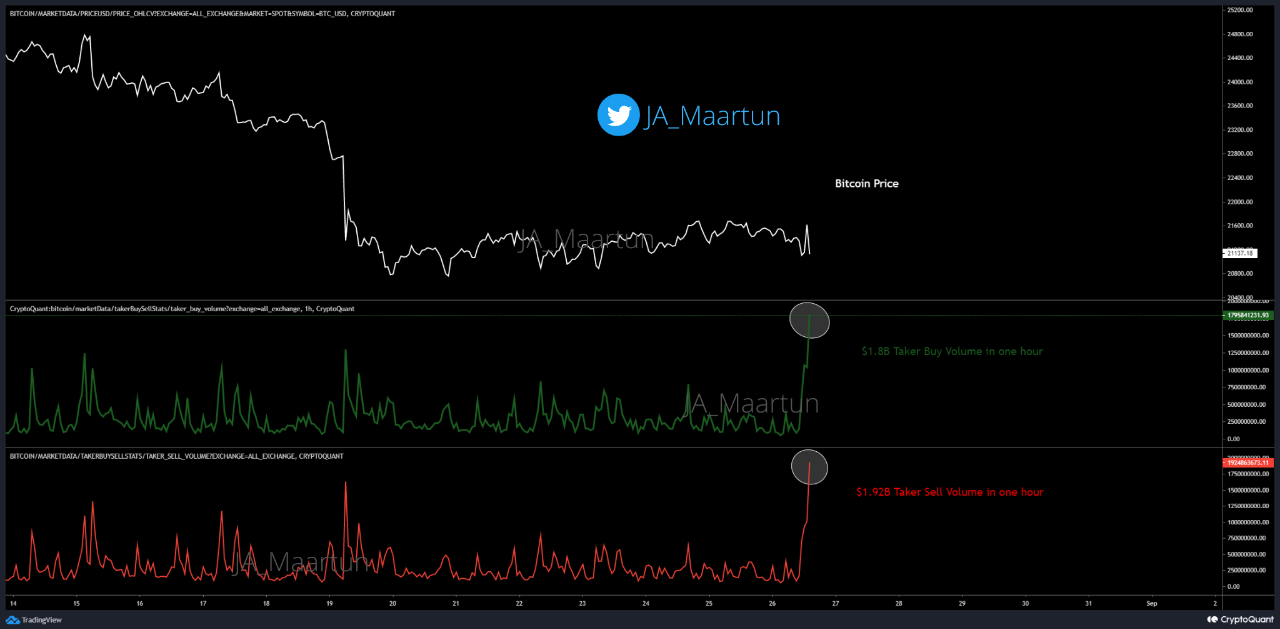

On-chain data shows both the Bitcoin taker buy and taker sell volumes registered large spikes over the past day as the price goes through volatility.

As pointed out by an analyst in a CryptoQuant post, both the BTC taker buy and taker sell volumes hit more than $1.8 billion yesterday.

The “taker buy/sell volume” is an indicator that measures the Bitcoin long and short volumes on derivatives exchanges. The metric distinguishes between these two volumes based on whether the transaction occurs at the ask price (taker buy) or the bid price (taker sell).

When these volumes are high, it means the exchanges are receiving a large amount of orders right now. This kind of trend usually leads to higher volatility in the price of the crypto.

On the other hand, low values suggest there is little activity in the market at the moment, which can result in a more stale price action for BTC.

Now, here is a chart that shows the trend in the Bitcoin taker buy and taker sell volumes during the last couple of weeks:

The values of the two metrics seem to have shown large spikes during the past day | Source: CryptoQuant

As you can see in the above graph, the Bitcoin taker buy and taker seller volumes have seen quite sharp increases recently.

These spikes have come just after the Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell delivered an interest rate warning in a speech yesterday.

The taker buy volume took just an hour to reach $1.8 billion, while the taker sell volume rose even higher at around $1.92 billion.

The value of Bitcoin observed a drop below the $20k level some time after this elevation in the market activity. Currently, it’s unclear whether this was it for the volatility or if the coin will continue to see more sharp price action in the near future.

At the time of writing, Bitcoin’s price floats around $19.8k, down 6% in the last seven days. Over the past month, the crypto has lost 6% in value.

The below chart shows the trend in the price of the coin over the last five days.

Looks like the value of the crypto has sharply declined over the last twenty-four hours | Source: BTCUSD on TradingView

After moving mostly sideways during the past week, Bitcoin seems to have broken out of the range today as the crypto has dipped below the $20k mark for the first time since the middle of July.

Featured image from Kanchanara on Unsplash.com, charts from TradingView.com, CryptoQuant.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Kuroda Pledges Loose Policy Until Price, Wage Gains Sustainable Bloomberg

Some 24 million British households received distressing news on Friday: Starting Oct. 1, they will be paying 80 percent more for energy, or a total of 3,549 pounds over the course of a year for a typical British home.

The amount of the increase was set by a government regulator called Ofgem (for Office of Gas and Electrical Markets). Its job is to figure out how much cost companies that supply energy to households can pass along to consumers, while ensuring that the companies play fair.

Ofgem determines what suppliers can charge households through a complex calculation that includes setting a price per unit of natural gas and electricity, as well as a series of other charges, like subsidies for clean energy and networking and operating costs, that make up a bill.

Although widely described as a price cap, the figure released by Ofgem is an estimate of what a typical household would pay over a year. A bill may exceed or fall short of the estimate depending on how much energy a household used, as well as its location and other factors. The cap used to be updated every six months, but starting in October it will be reset every three months.

Ofgem said the increase announced on Friday was nearly entirely due to higher wholesale energy costs, largely stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In a typical bill starting in October, wholesale energy costs will represent about 70 percent of the total.

The suppliers are permitted to make a 1.9 percent profit under the pricing program. Ofgem called such profit levels “modest” on Friday, although it is looking into whether they are too high. The regulator noted that “most domestic suppliers are currently not making a profit.”

Energy, though, is currently a tale of haves and have-nots. Producers of oil and gas like BP and Shell have reported record profits, while consumers and some businesses are taking a beating. Dozens of small start-up utilities have gone bust in Britain, but generators of electricity with largely fixed costs, like nuclear plants and wind and solar farms, are most likely “doing well” from the high prices, said Martin Young, an analyst at Investec, an investment bank.

Announcements like those on Friday of sudden, huge surges in prices have led some commentators to say the regulator and the price caps are not functioning. “The price cap doesn’t work,” said David Howell, a former British energy minister who is now a member of the House of Lords.

As things stand, the reality is that energy prices must be either paid by consumers or somehow subsidized by taxpayers for those who can’t afford them.

After lagging behind the rest of the nation for several weeks, average gas prices in New Jersey finally dropped below $4 a gallon Friday. It’s the first time they’ve been that low since March.

On Friday, AAA reported the statewide average price for a gallon of regular dropped to $3.99 after stubbornly remaining higher than the national average — which dipped below $4 on August 9 — for several weeks.

“Break out the champagne,” said Robert Sinclair, a AAA Northeast spokesman, who tracks gas prices. “Gasoline prices are following crude oil prices lower, which continue to drop due to investors worried about global inflation and with it, lower demand for petroleum products.”

Crude oil prices roller coastered up and down on commodities markets through August before settling on a price of $92 a barrel on Thursday, NASDAQ reported.

Adding to the lower demand for gas was a cause and effect of high gasoline prices which peaked in mid-June, resulting in drivers staying close to home, he said. Remember one year ago, the average for regular was $3.18 a gallon, AAA reported.

“This corresponded with AAA survey results from March where 60% of drivers said $4 per gallon was the pain point and 75% said $5 was the pain point,” Sinclair said. “The main reaction to higher prices? Drive less.”

What took New Jersey so long to follow the national price drop was the lack of oil refining capacity in the Northeast, meaning that gasoline has to be shipped from somewhere else, said Patrick De Haan, GasBuddy.com head of petroleum analysis.

“The Northeast continues to be dogged by refinery issues and imports and has struggled as of late,” he said. “It’s the supply issue and import levels not being adequate. You’ll pay until it’s solved.”

The permanent closure of a Philadelphia-based refinery after a fire and the shutdown of a Canadian refining plant due to COVID-19 outbreak are among the reasons New Jersey and Northeast gas prices stayed higher, De Haan said.

Besides shipping gas from other regions of the country, the Northeast also imports gasoline from Europe, contributing to higher prices here, he said. Adding to price pressure is the region is required by the U.S. EPA to use pricier reformulated gas to reduce air pollution during the summer, he said.

State gas taxes are less of a factor because they don’t change as frequently, he said. However, New Jersey’s gas tax rate does change based on whether it meets an annual target of $2 billion in revenues to fund the state Transportation Trust Fund.

In August 2021, state officials announced an 8.3 cent per gallon cut in the gas tax rate, which took effect on Oct. 1, 2021. Despite that reduction, drivers complained that they didn’t see the reduction in pump prices.

While $3.99 is the average price, GasBuddy.com reported 15 gas stations in the state with prices ranging from $3.49 a gallon to $3.63. Gas Buddy uses a combination of crowd sourcing and gas station surveys in price reporting.

Even name brand stations could be found selling under the $3.99 mark, including a mini price war seen on Route 27 in Iselin where a Shell was selling regular at $3.75 cash, a nearby BP priced it at $3.76 a gallon and a Delta had a $3.71 per gallon price on Thursday.

Could prices go lower? That depends on nature, global politics and driving, experts said.

“I see more downward pressure. It’s a question of nature and whether we see hurricanes, and geo-political tensions,” De Haan said. “Prices should fall because summer is in its final innings and the switch to winter blend gas happens in three weeks.”

Besides a gulf coast hurricane season that could affect refineries and oil drilling rigs, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, OPEC, could take action that would put the brakes on price drops.

“It could be offset by OPEC, who this week said it wants to...reduce (oil) production because of the global economy,” he said. “That’s one of the wild cards.”

Experts doubted the price drop was significantly impacted by the upcoming mid-term elections in November.

“Political manipulation can not do much to affect prices,” Sinclair said. “If there were a sudden cessation of the war in Ukraine, that would go a long way to restoring political and market stability and lower prices, but that seems a long shot right now.”

Gas price fluctuations are cyclical, based on the time of year and increases or decreases in driving, which influence demand, De Haan said. Prices increase in the spring, rise through the summer with vacation season and drop off in fall and winter, when people drive less, he said.

“Market forces always override people’s feelings and beliefs,” De Haan said. “Cyclical demand is higher in spring than in the fall.”

Our journalism needs your support. Please subscribe today to NJ.com.

Larry Higgs may be reached at lhiggs@njadvancemedia.com.

In this article

DETROIT – Ford Motor is hiking the starting prices of its electric Mustang Mach-E crossover by more than $8,000 for some models, as it reopens order banks for the 2023 model year.

The company on Thursday said the markups – ranging between $3,000 and $8,475, depending on the model and battery – are due to "significant material cost increases, continued strain on key supply chains, and rapidly evolving market conditions."

The Mach-E is the latest electric vehicle to experience a price increase, as raw material costs for batteries for electric vehicles more than doubled during the coronavirus pandemic.

The starting prices for the 2023 Mustang Mach-E will now range from about $47,000 to $70,000, up from roughly $44,000 to $62,000 for the 2022 model year. Prices exclude taxes and shipping/delivery costs.

Ford earlier this month also raised the starting prices of its electric F-150 Lightning pickup by between $6,000 and $8,500, depending on the model. The automaker cited similar reasons for those increases, specifically related to raw materials such as lithium, cobalt and nickel that are used in batteries for the vehicles.

Others automakers including General Motors, Rivian, Lucid and Tesla also significantly raised prices on their newest electric vehicles.

In addition to the new pricing, Ford said it changed options and increased capabilities for some Mach-E models. It also is increasing shipping charges on the Mach-E by $200 to $1,300 on all models.

Ford said the higher prices will go into effect for new orders placed starting Tuesday, when order banks reopen.

Customers who have existing, unscheduled 2022 model year orders will receive a "private offer" to convert to a 2023 model year vehicle, the company said. It's not immediately clear what price those customers would be offered.

Thank you for the opportunity to speak here today.

At past Jackson Hole conferences, I have discussed broad topics such as the ever-changing structure of the economy and the challenges of conducting monetary policy under high uncertainty. Today, my remarks will be shorter, my focus narrower, and my message more direct.

The Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC) overarching focus right now is to bring inflation back down to our 2 percent goal. Price stability is the responsibility of the Federal Reserve and serves as the bedrock of our economy. Without price stability, the economy does not work for anyone. In particular, without price stability, we will not achieve a sustained period of strong labor market conditions that benefit all. The burdens of high inflation fall heaviest on those who are least able to bear them.

Restoring price stability will take some time and requires using our tools forcefully to bring demand and supply into better balance. Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth. Moreover, there will very likely be some softening of labor market conditions. While higher interest rates, slower growth, and softer labor market conditions will bring down inflation, they will also bring some pain to households and businesses. These are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation. But a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain.

The U.S. economy is clearly slowing from the historically high growth rates of 2021, which reflected the reopening of the economy following the pandemic recession. While the latest economic data have been mixed, in my view our economy continues to show strong underlying momentum. The labor market is particularly strong, but it is clearly out of balance, with demand for workers substantially exceeding the supply of available workers. Inflation is running well above 2 percent, and high inflation has continued to spread through the economy. While the lower inflation readings for July are welcome, a single month's improvement falls far short of what the Committee will need to see before we are confident that inflation is moving down.

We are moving our policy stance purposefully to a level that will be sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent. At our most recent meeting in July, the FOMC raised the target range for the federal funds rate to 2.25 to 2.5 percent, which is in the Summary of Economic Projection's (SEP) range of estimates of where the federal funds rate is projected to settle in the longer run. In current circumstances, with inflation running far above 2 percent and the labor market extremely tight, estimates of longer-run neutral are not a place to stop or pause.

July's increase in the target range was the second 75 basis point increase in as many meetings, and I said then that another unusually large increase could be appropriate at our next meeting. We are now about halfway through the intermeeting period. Our decision at the September meeting will depend on the totality of the incoming data and the evolving outlook. At some point, as the stance of monetary policy tightens further, it likely will become appropriate to slow the pace of increases.

Restoring price stability will likely require maintaining a restrictive policy stance for some time. The historical record cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy. Committee participants' most recent individual projections from the June SEP showed the median federal funds rate running slightly below 4 percent through the end of 2023. Participants will update their projections at the September meeting.

Our monetary policy deliberations and decisions build on what we have learned about inflation dynamics both from the high and volatile inflation of the 1970s and 1980s, and from the low and stable inflation of the past quarter-century. In particular, we are drawing on three important lessons.

The first lesson is that central banks can and should take responsibility for delivering low and stable inflation. It may seem strange now that central bankers and others once needed convincing on these two fronts, but as former Chairman Ben Bernanke has shown, both propositions were widely questioned during the Great Inflation period.1 Today, we regard these questions as settled. Our responsibility to deliver price stability is unconditional. It is true that the current high inflation is a global phenomenon, and that many economies around the world face inflation as high or higher than seen here in the United States. It is also true, in my view, that the current high inflation in the United States is the product of strong demand and constrained supply, and that the Fed's tools work principally on aggregate demand. None of this diminishes the Federal Reserve's responsibility to carry out our assigned task of achieving price stability. There is clearly a job to do in moderating demand to better align with supply. We are committed to doing that job.

The second lesson is that the public's expectations about future inflation can play an important role in setting the path of inflation over time. Today, by many measures, longer-term inflation expectations appear to remain well anchored. That is broadly true of surveys of households, businesses, and forecasters, and of market-based measures as well. But that is not grounds for complacency, with inflation having run well above our goal for some time.

If the public expects that inflation will remain low and stable over time, then, absent major shocks, it likely will. Unfortunately, the same is true of expectations of high and volatile inflation. During the 1970s, as inflation climbed, the anticipation of high inflation became entrenched in the economic decisionmaking of households and businesses. The more inflation rose, the more people came to expect it to remain high, and they built that belief into wage and pricing decisions. As former Chairman Paul Volcker put it at the height of the Great Inflation in 1979, "Inflation feeds in part on itself, so part of the job of returning to a more stable and more productive economy must be to break the grip of inflationary expectations."2

One useful insight into how actual inflation may affect expectations about its future path is based in the concept of "rational inattention."3 When inflation is persistently high, households and businesses must pay close attention and incorporate inflation into their economic decisions. When inflation is low and stable, they are freer to focus their attention elsewhere. Former Chairman Alan Greenspan put it this way: "For all practical purposes, price stability means that expected changes in the average price level are small enough and gradual enough that they do not materially enter business and household financial decisions."4

Of course, inflation has just about everyone's attention right now, which highlights a particular risk today: The longer the current bout of high inflation continues, the greater the chance that expectations of higher inflation will become entrenched.

That brings me to the third lesson, which is that we must keep at it until the job is done. History shows that the employment costs of bringing down inflation are likely to increase with delay, as high inflation becomes more entrenched in wage and price setting. The successful Volcker disinflation in the early 1980s followed multiple failed attempts to lower inflation over the previous 15 years. A lengthy period of very restrictive monetary policy was ultimately needed to stem the high inflation and start the process of getting inflation down to the low and stable levels that were the norm until the spring of last year. Our aim is to avoid that outcome by acting with resolve now.

These lessons are guiding us as we use our tools to bring inflation down. We are taking forceful and rapid steps to moderate demand so that it comes into better alignment with supply, and to keep inflation expectations anchored. We will keep at it until we are confident the job is done.

1. See Ben Bernanke (2004), "The Great Moderation," speech delivered at the meetings of the Eastern Economic Association, Washington, February 20; Ben Bernanke (2022), "Inflation Isn't Going to Bring Back the 1970s," New York Times, June 14. Return to text

2. See Paul A. Volcker (1979), "Statement before the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress, October 17, 1979," Federal Reserve Bulletin, vol. 65 (November), p. 888. Return to text

3. A review of the applications of rational inattention in monetary economics appears in Christopher A. Sims (2010), "Rational Inattention and Monetary Economics," in Benjamin M. Friedman and Michael Woodford, eds., Handbook of Monetary Economics, vol. 3 (Amsterdam: North-Holland), pp. 155–81. Return to text

4. See Alan Greenspan (1989), "Statement before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate, February 21, 1989," Federal Reserve Bulletin, vol. 75 (April), pp. 274–75. Return to text

Reverberations from the war in Ukraine have “distorted” the market for natural gas, forcing energy prices up.

Energy traders in Europe are witnessing price increases that are hard to fathom. Natural gas, which is used to generate electricity and heat, now costs about 10 times more than it did a year ago. Electricity prices, tied to the price of gas, are also several times higher than what used to be considered normal.

As Russia tightens the screws on flows of gas, the energy markets are locked in a relentless upward climb. This week, benchmark European natural gas prices hit a series of records after Gazprom, the Russian gas giant, said it would temporarily shut a key pipeline to Germany at the end of August — a move that has further stoked market fears.

Electricity prices have been extremely volatile. In Britain, the wholesale price of a megawatt-hour of electricity (enough to supply about 2,000 homes for an hour) hit a record daily average of about 500 pounds, or $590, early this week, roughly five times the level of last August, according to Rajiv Gogna, a partner at LCP, a consulting firm.

In some countries, there is little cushion between these wholesale prices and what consumers must pay in their monthly bills. On Friday, the British electricity regulator will reset an energy price cap that is widely expected to almost double the price that a typical British household would pay in the coming months for electricity and gas, to about £3,500 a year. The jump reflects steadily increasing costs for gas and electricity.

Further price increases in Britain and elsewhere are anticipated, adding to hardship and bolstering arguments for government intervention.

Price of benchmark European natural gas contracts

Driving the prices is a fear that Europe will run out of gas this winter. Russia has slashed gas flows to Germany and other countries. Even before the coming three-day shutdown, Nord Stream 1, a key conduit of fuel to Germany, has been flowing at only 20 percent of capacity. These cutbacks are forcing gas providers to buy gas on the spot market at higher and volatile prices than under longer-term Gazprom contracts.

In many countries, gas and electric power prices are closely intertwined, a relationship that has added to Europe’s woes. Although there are several ways to generate electricity — such as coal, nuclear, hydroelectric, wind and solar — the price of natural gas is hugely influential in setting electricity prices because gas-burning generators are most often paid to go into service when a power grid like Britain’s needs more electricity.

“Natural gas is the driver for the European electricity price,” said Iain Conn, a former chief executive of Centrica, a large British utility.

This relationship makes Europe more vulnerable to Russia’s energy weapon. Unlike the United States, which has an ample surplus of natural gas to export, thanks to shale drilling, Europe needs to import the bulk of its gas, with Russia traditionally supplying around one-third. Well before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, European gas and power prices rose over supply concerns.

“When natural gas supplies get tight, the electricity market gets extremely exercised,” said Mr. Conn, who is also a former senior executive of BP, the energy giant.

Other factors are pushing up power prices, including low river levels that are impeding shipments of fuel to coal-fired plants that Germany and other governments want to fire up to replace gas.

The short answer is, a lot. European Union countries like Germany and the Netherlands are racing to fill gas storage facilities as a buffer against a possible complete cutoff of Russian gas this winter. Governments have also moved to secure more supplies in the form of liquefied natural gas from the United States and elsewhere and prodded energy companies to build new terminals for receiving the chilled fuel, often with state financing.

Britain and other countries are providing financial aid to consumers, although not enough to compensate for the huge increased costs that households face.

A wide spectrum of politicians, consumer advocates and even energy industry executives are calling for governments to do much more.

“What’s increasingly clear is these tough conditions for U.K. households are going to get much, much worse before they get better,” said Keith Anderson, the chief of executive of Scottish Power, a British utility, in a recent open letter. Mr. Anderson suggested that the government intervene to cover the rising cost of gas, a proposal that could cost tens of billions of pounds over the next two years.

Government mandates are already forcing markets to behave in a way that would seem bizarre in other circumstances.

In a normal market, for instance, high prices would lead to selling gas, not stockpiling it. But the pressure to fill gas storage facilities, backed by the government directives, has forced energy companies to buy — and keep buying — expensive gas, driving the price ever higher.

In one sense, the storage program has been very successful. Salt caverns and other locations in Germany are more than 80 percent full, on track to meet a target of 95 percent by Nov. 1.

But the urge to buy protection for the winter is driving up prices, and is doing some of the economic damage it was intended to prevent, analysts say.

“The market is totally debased and distorted now,” Henning Gloystein, a director at Eurasia Group, said. “If you were a semi-sensible trader, you would sell all the gas you have in storage now out into the spot market and make an absolute killing,” he added. The governments in Germany and elsewhere, though, are insisting on other priorities.

Indeed, pressure is growing for even more government intervention.

Already, many small British energy suppliers have gone bankrupt, leading to higher costs for both the government and consumers. France is taking full control of EDF, the large utility and builder of nuclear plants.

On Aug. 17, Uniper, one of Germany’s largest gas utilities, reported a loss of more than 12 billion euros ($12 billion) for the first half of the year, attributing much of the deficit to the impact of having to replace gas contracted from Gazprom but not delivered at higher market prices. The company agreed last month to a bailout, which includes the government’s taking a large equity stake in the company.

“We at Uniper have de facto become a pawn in this conflict,” said Klaus-Dieter Maubach, the company’s chief executive, referring to the war in Ukraine.

Analysts say that so far these technologies are helping only marginally to lower prices, because in wholesale electricity markets natural gas remains the key determinant in power prices. Chris Matson of LCP estimated that in 2021 Britain’s power prices were determined by gas more than 90 percent of the time, even though the fuel accounted for only about 40 percent of total generation.

Some analysts say it is time to redesign power markets to reflect the growing amount of wind and solar energy on European electrical grids. Unlike gas and coal generators, whose costs are largely determined by fuel prices, these renewable technologies have very low and steady operating costs. Their fuel is essentially free.

“What we need is a better market design that is less reliant on natural gas power plants to set the prices,” said Rahmat Poudineh, a senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. “It is likely that we can have a situation where electricity prices are lower than this,” he added.

Britain and other countries are considering revamping their energy markets. It is unlikely, though, that fundamental changes can be pushed through in time to help this winter.

[unable to retrieve full-text content] Companies' reluctance to roll back price rises poses US inflation risk Financial Times from...